- 1. Twin-bar tunes (ex.1-11, №1-58)

- Twin-bar tunes based on the g,-c bichord

- Twin-bar tunes based on rotating motifs

- Twin-bar tunes with descending/hill-shaped lines

- Motifs with a downward leap at the end of the line

- Motivic processes

- 2. Tunes moving on Ionian scales (ex.12-24, №59-164))

- Laments and their relatives

- Two-lined tunes of Major character with higher main cadences and their four-lined relatives

- Four-lined tunes of Major character

- 3. Aeolian tunes (ex.25-36, №165-238)

- Laments and related tunes

- Aeolian tunes with higher main cadence

- Four-lined tunes of Minor character

- Valley-shaped, ascending or undulating first line

- 4. Caramazan religious tunes (ex.37-41, №239-326)

- 5. Tunes of domed structure (ex.42-43, №327-332)

My folk music collecting trips to Kyrgyzstan

Obviously, an all-round mapping of the folk music of Kyrgyzstan would have been illusory, but the exploration of some major areas and the comparison of the tunes of tribes living there appeared feasible. I took the first steps in September 2002.

At first I planned to collect and compare the music of tribes in two areas. One was Issyk-kul with the Buğu tribe; the choice of this tribe was supported by their great past and Aitmatov’s famous novel, “The White Steamboat”. The other area was Narın county with the Çerik, Moñoldor and Sarıbağış tribes living there. Narın is one of the most isolated, poorest and hence most traditional areas of Kyrgyzstan. The north is under strong Russian and Kazakh influence, in the south the Tajik and Uzbek influence is powerful, while in southern Narın county far less foreign influence reaches the Kyrgyz living in the mountains some 150 km from the Chinese border. Besides, on the other side of the border Kyrgyz people live, too, who migrated there.

With the help of Tibor Tallián, director of the Institute for Musicology, we initiated a contact between the Hungarian and Kyrgyz Academies of Sciences. After a long time a letter of invitation arrived from the Kyrgyz Academy, but I waited for a formal invitation required for a visa in vain. I knew the Hungarian ambassador to Almati, Miklós Jaczkovits, the representative of the Hungarians in Kyrgyzstan as well. He promised I would get the visa at Bishkek airport.

About my collecting in Issyk-kul in 2002

I started in September 2002. It takes long to get from Budapest to Bishkek: two hours to Istanbul, a few hours‘ waiting at Istanbul airport, then a five-hour flight to Bishkek. I only stayed a few days in the Kyrgyz capital, chiefly organizing my fieldwork. I contacted the Kyrgyz Academy and the Kyrgyz-Turkish Manas University, and I got acquainted with Ulanbek Tınççılık uulu, who accompanied me to Narın in 2002 and 2004 and to Talas in 2004. Without the cooperation of this talented and clever person my collecting trips could not have had this much success.

The journalist father of Turkologist Dávid Somfai Kara’s Kyrgyz wife recommended me a young man, Tilek from the Buğu clan around Issyk-kul, who became my driver and companion in 2002.

The first field trip was in September 2002 around the village Barskoon in Issyk-kul. Kyrgyz is a close relative, almost dialect of Kazakh, but unlike the Kazakh who strongly reduce the vowels just like the Mongols, the Kyrgyz nicely pronounce them. It was thus easier to communicate in the vernacular in Kyrgyzstan. In a few days I could improve my Kyrgyz enough to be able to control the process of collecting, understood what was said and could put questions to the informants.

For the Issyk-kul field research in the villages, we set out from Barskoon. I can’t present the entire logbook but let me acquaint you with the chronicle of an “average” day.

I lived in the house of Tilek’s parents in Barskoon. However tiring it may be, it is very useful for a researcher to be constantly in a vernacular milieu. After the fieldwork, he can discuss the collecting results and begin planning the next day’s work.

After an early breakfast we left for some nearby village. We collected materials at houses, along the road, in yurts, at pastoral quarters. The latter places are fascinating even if one fails to collect anything. On 25 September, on the 8th day Tilek suggested visiting his uncle who was in the summer pasture of the village with the livestock in the mountains around Barskoon. The yayla was far, we reached it after a good two hours‘ climbing. The herdsman was off looking for some stray cows. His family offered us fresh milk, just baked cake and home-churned butter. You can’t eat such delicacies even in luxury restaurants in large cities. The bright sunshine and spectacular panorma were enchanting – Kyrgyzstan could indeed be the Switzerland of the East for its natural endowments. We also tried out the horses and met with a terrifying thick pitch black snake two and a half meters in length which Tilek and the others chased and caught laughing. A cautious researcher as I am, I didn’t take part in this amusement.

Later we chatted with the cowherd’s wife and recorded songs, then the young herder’s vocal signals which herdsmen yell to communicate over large distances. We were soon to test our new knowledge as the uncle’s greeting sound signal was heard and came gradually closer.

The herdsman was a short, sturdy figure with smiling eyes and full of kindliness. He was overjoyed to greet his nephew Tilek and us, his guests. While he was having dinner, Tilek signalled that I should give him the vodka. I very seldom give alcohol to informants, the reason not being one of the seven deadly sins, avarice, but the recognition that an intoxicated person only thinks he/she sings nicer than in a sober state. But I had no other choice, so I gave it to him and it soon began gurgling down the uncle’s throat.

Herdsman Abdıldayev Şükür was born in the village of Barskoon in 1933. He sang the “Kök-Corgo” song, Caramazan tunes, details from the Manas epic, songs about Barskoon and the Çoñ-Cargılçak mountain pasture, songs of youth and love, even laments and bride’s farewell song. The latter two to dissuade us from urging his wife to sing women’s song. In the evening we had to outpace falling darkness downhill, for in the mountains there are a lot of wolves, it isn’t advisable to be on the road at night.

All in all, I recorded some 220 tunes around Issyk-kul at 25 localities from 84 informants. A great majority are traditional folksongs, but there are some Soviet-era songs as well. The corpus is supplemented by instrumental tunes, information on the tunes, photos, pictures of village life and interviews.

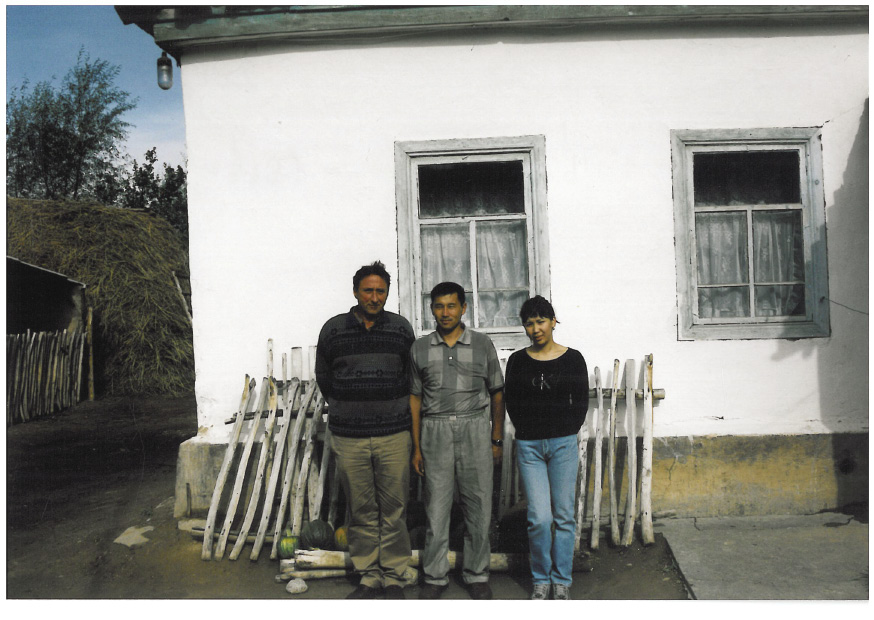

Picture 2 The collecting team by Issyk-kul (the author of the book is on the left)

Picture 2 The collecting team by Issyk-kul (the author of the book is on the left)

Bishkek

In Bishkek I had two collecting sessions. I recorded the songs of a woman from around Osh. The other informant was a kobuz player and singer called Nurak Abdirahmanov. The stronger Muslim faith of the southern Kyrgyz populace around Osh and their different culture make them particulary noteworthy. Later I complemented this southern material with tunes from Dávid Somfai Kara’s collection.

Picture 3 Kyrgyz shepherd in his tent on the summer pasture of Barskoon

Picture 3 Kyrgyz shepherd in his tent on the summer pasture of Barskoon

My fieldwork in the Narın region in 2002

As I mentioned, before the first field trip I made the acquaintance of Ulanbek Tınççılık Uulu from Narın. We chose At-Başı as our center in poor, isolated Narın county little exposed to foreign influence. We collected material there and in 15 nearby villages. Organization was extraordinary. In the evening, the father of my companion telephoned to the village to be visited the next day and around 10 am as we arrived several excellent informants were waiting for us. We began work with them at a central location and continued at the houses. In terms of folk music collection, we fared better here than around the Issyk-kul. This is evidenced by the amount of 330 songs and more important still, by the musical quality of the material. The 330 songs were collected in 10 villages and in the yurts of summer quarters, from 86 men and women.

About my field research in 2004

Already in 2002 I decided to continue research around At-Başı as the music of the 15 villages surrounded by mountains seemed exhaustible during another complementary expedition. I hoped to have a detailed map of the music of this area in this way. I also planned a longer field research in Talas in 2004. Complemented with items from other collectors‘ southern material the corpus I hoped to have at the end of the expeditions seemed to be a reliable material to represent the entire Kyrgyz vocal folk music.

Returning was also necessitated by the ever newer, so-far unheard tunes cropping up until the very last day of my fieldwork in Narın in 2002, in spite of the huge amount already recorded. The field research of 2004 took place in April and May. My Kyrgyz companion was again Ulanbek, with whom I toured the vicinity of At-Başı in 2002. A discharged policeman, his father used to be party secretary, who was now a journalist, a real Kyrgyz patriot who did not use his position to get rich but to defend his helpless fellows. He is held in great esteem to this day. Typically, as a former functionary, he sang the religious ezan.

After arrival in 2004 I spent a few days sightseeing in Bishkek. Ulanbek arranged my registration with the police and we left one afternoon for At-Başı by car. Marvelling at beautiful snowcapped mountains and chatting we hardly noticed the passing of time – we arrived around 10 pm, had dinner and went to bed.

At-Başı was founded in 1810 as a stopover along the silk road. Around it, in a beautiful valley of the Tien-Shan there are 16 villages. The former nomads were settled in these villages by force in the 1920s-30s. The livestock were confiscated from the bays and given to the poor, or more precisely kolkhozes were founded. The bays were exiled to Ukraine or the Caucasus – hardly any of them returned. Earlier this area was mainly peopled by members of the Çerik tribe; those of the Sarıbağış and Moğoldor tribes settled here later. There are intermarriages between the tribes, they coexist without considerable tensions.

We left to collect about 8 every morning. Again the father made a phone call to the village and by the time we arrived some 10-15 elderly men and women had been waiting for us at the culture centre in folk costumes: collecting could begin. This is surely the cherished dream of every folk music researcher: when a singer has run short of the songs, another picks up the thread; when somebody goes home, another one replaces him or her. After the work at the culture centre we continued at the people’s houses. It was not rare to collect some 70 songs a day.

Let me only reproduce the schedule of a single day again. Early on 25 April we visited a gözaçık or “seer”. Uusoon kızı Turdububu belonged to the Çerik tribe and was born in the village of Kazıbek. She said prophecies of the past and future, of expectable bad and good events. She also helped the police with their investigations and she also cured people. She knew the Quran well and said prayers. In addition to prophecying, she made toy figures for a living. She predicted I would live long and said that a benevolent spirit was supporting me from the water.

After the seer we collected some material from a few men and women in At-Başı: several laments, antiphonal songs, children’s songs, songs sung to children, young girls‘ songs, love songs, folksongs, Caramazan and a few more modern tunes enriched our collection. Most singers were from the Çerik tribe. We visited the market, too, but despite promises, we could not collect there, so we returned to the original venue. Asanova Alisa, the mother of ten children, sang to us 20 so-far unheard songs. As for genre, they were lullabies, laments, life songs (hayat şarkısı), young people’s songs, bride’s farewell, Caramazan, Bekbekey, song sung to a husband going off to war, plaintive songs, rain-making song, songs sung during work in the fields, antiphonal songs, lads‘ songs and other folksongs. This body of tunes exemplified nearly every important genre, also providing many ingenuous variants and a few tune types we had not heard earlier. It was a great joy because in the previous days we had only managed to record variants of already known tunes. We again got home about 6-7, hungry as a wolf as usual. We had dinner, reviewed the day’s crop and planned the next day’s program.

After the work at At-Başı we went to Bishkek on 28 April, attending the Opera there with our Turkish friends. We overnighted at the Dostluk Hotel: a good bathroom and comfortable bed at long last! The guests were mainly Russians and English-speaking foreigners – no wonder as a day cost there the monthly salary of a native person. Kuday buyursa – God willing, we’re off to Talas tomorrow!

Picture 4 Kyrgyz aksakals

Picture 4 Kyrgyz aksakals

Field research in the Talas area, 2004

We left for Talas on 29 April. We first planned to go across Kazakhstan, but I had no visa for repeated entry into the country, so we were turned back at the border and had no other choice but cross the snowcapped Talas Ala-Too (Alatau) mountain. The old tyres of our old car were hard put to negotiate the icy road with snow drifts from the blizzards; we had to get out and push the car several times. It was a great relief to arrive at “Paris” – the far from glamorous restaurant on the other side of the mountain. We had manti and porpor, and rolled on to Talas, the seat of Talas county.

In the morning the first thing was to find a young man to help us with field research. At first we talked to local teachers who knew hardly any tunes beside Russian-style songs (as was typical of the local intellectuals in general). They even performed the Caramazan tunes and laments in a distorted, artificial manner. We had to explain again what we actually wanted, but this time it was easier because Ulanbek already knew it.

In Talas and the nearby villages we carried on highly successful field research, recording some 70 songs a day. We collected 336 tunes in 11 villages, a real feat. Poverty is great in this region, too; there was either no water (e.g. Taldı-Bulak) or no electricity, the toilet was at the end of the street at several places. We had an easy job, as the elderly were glad to come together and sing one tune after the other.

The research trip of 2004 was perhaps more successful than the 2002 research: I recorded 576 tunes from 216 singers at 22 locations. The strong variability of the tunes was conspicuous: it is one of the fundamental features of Kyrgyz instrumental and vocal musical culture. It cannot be a sign of decline or failing memory because it also characterized the performance of the excellent singers and professional instrumentalists. It was important to observe that the recorded tunes showed no noteworthy difference from the stock of other areas.

I collected in three major regions (At-Başı, Narın and Talas) in 2002 and 2004, chiefly recording songs which the Kyrgyz themselves regarded as belonging to their folk culture. They included tunes with ancient roots, religious songs and some Soviet hits; the latter I only recorded and present briefly here for the sake of contrast. In Kyrgyzstan the powerful decline of folk culture began in the thirties, when the kolkhozes came to be established. Several things (e.g. their headgear) were banned, and although folksongs were not prohibited, they lost their nurturning medium. It is a miracle that they lived to see the 21st century at so many places. Those who were children in the 1930s and ‘40s – and were 70-80-year old at the time of my field research – still had first-hand experience or at least strong memories of living oral culture. This can’t be said of the generation that came after them – the folk culture is gone with communism.

Today, only relics of the past can be collected, yet this is the only possibility to complement earlier collections, and to document and scientifically describe the contemporary rural musical repertory. On this basis attempts can be made to reconstruct the vocal folk music of this formerly nomadic people. It enhances the value of my research that in Kyrgyzstan no musical collection with a view to areal and tribal aspects had been conducted. In addition to musical conclusions, the recorded material is therefore suitable for making linguistic and cultural inferences.