János Sipos

Essays on the Folksongs of Turkic People

Technical preparation of the E-book: Adrienn Ádám

Programming: Zsolt Kemecsei

ISBN: 978-615-5167-64-5

© HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities Institute for Musicology 2024

© János Sipos 2024

Using the E-book

This E-book is an electronic version of the volume quoted above. You can click on the symbol ![]() to listen to the sound and click on

to listen to the sound and click on ![]() to see video recordings.

to see video recordings.

Using the e-book is facilitated by a tool box in the lower left corner: after the search bar, the second icon jumps to the table of contents, while the third icon allows you to print the book or part of it.

About the author

Prof. Dr. János Sipos is professor at the Liszt University of Music, the Hungarian Representative of the International Council of Traditional Music, senior research fellow of Institute for Musicology, and Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts.

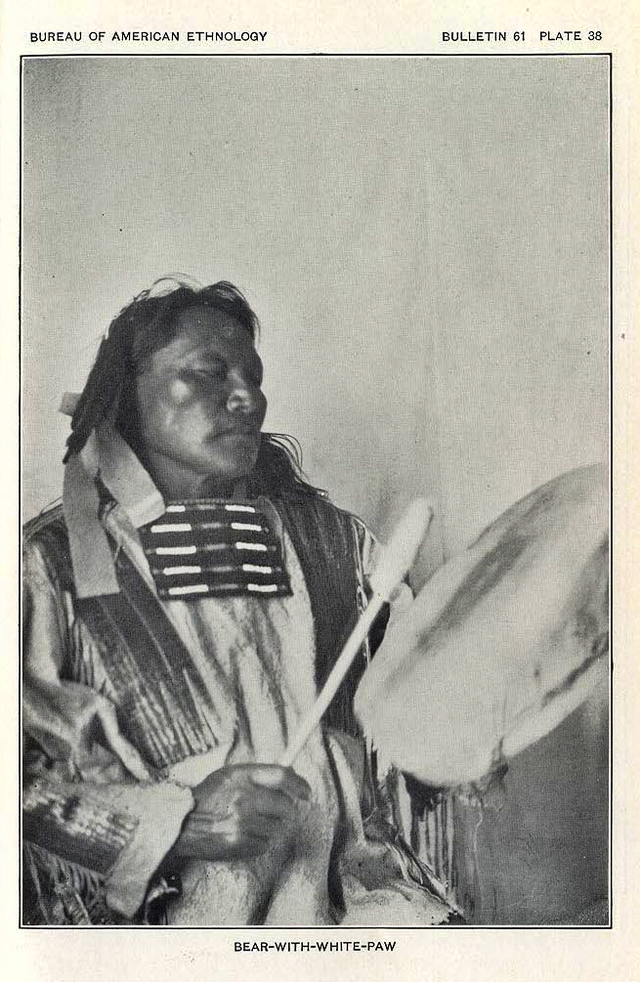

His main research area is the comparative study of the folk music of Turkic speaking pople and also exploring the Hungarian relations. His collecting work began in 1987, where Béla Bartók stopped in 1936, and since then he has collected, recorded and analyzed more than ten thousand Turkish, Azeri, Turkmen, Karachay, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Navajo and Dakota melodies. His 18 books, 168 articles and hundreds of hours of video and audio recordings can be viewed at www.zti.hu/sipos.

Contents

A Folk Music Research Series Among Turkic People (1936-2019)

A Folk Music Research Series Among Turkic People (1936-2019) About the Folksongs of Some Turkic People

About the Folksongs of Some Turkic People Dakota Folk Songs and their Inner-Asian Connection

Dakota Folk Songs and their Inner-Asian Connection Ancient Hungarian musical styles and their connection to the folksongs of Turkic people

Ancient Hungarian musical styles and their connection to the folksongs of Turkic people An Inner Mongolian pentatonic fifth-shifting style and its relevance to Hungarian and

An Inner Mongolian pentatonic fifth-shifting style and its relevance to Hungarian andVolga-Region folk music

About the first analytic and comparative monograph written on the folk music of the

About the first analytic and comparative monograph written on the folk music of theKarachay-Balkar people

References

References Bibliography of János Sipos

Bibliography of János Sipos Endnotes

Endnotes

A Folk Music Research Series Among Turkic People (1936-2019)

Hungarian prehistory displays a peculiar duality of language and music: the language belongs to the Finno-Ugric family, while several pre-Conquest strata of the folk music are connected to Turkic groups. Intrigued by this phenomenon, Hungarian researchers launched thorough comparative examinations quite early; to mention but the most important scholars: Zoltán Kodály demonstrated Cheremis and Chuvash analogies in the first place; Lajos Vargyas carried out the comprehensive historical investigation of the folk music of the Volga-Kama region; Bence Szabolcsi demonstrated even broader international musical connections after surveying an enormous material; Katalin Paksa studied the eastern relations of our narrow-range tetra- and pentatonic tunes and László Dobszay with Janka Szendrei applying a novel approach to the Hungarian folk music material reviewed the international material in regard to the lament and psalmodic styles, among other things.

In keeping with the noblest traditions of Hungarian folk music research, investigations authenticated by fieldwork have been going on to this day parallel with theoretical research. Most important among them are Béla Bartók’s Anatolian collecting in 1936, László Vikár’s and Gábor Bereczki’s areal field research in the territory designated by the Volga, Kama, and Belaya rivers in 1957-1978, and my field research activity among several Turk ethnicities since 1987 till now.

At the beginning, the main goal of this research series was to explore the eastern relations of the Hungarian folk music, which gradually broadened into the areal research of the multi-ethnic Volga-Kama-Belaya region. I further expanded it into the comparative investigation of diverse Turkic-speaking groups living over the vast Eurasian territory. In the meantime, the study of Hungarian prehistoric connections was also going on.

It justifies research into Turkic folk music that these ethnic groups have long been playing salient roles in Asia, and without the exploration of their music the musical world of Eurasia cannot be comprehended. What makes this research even more interesting is the fascinating diversity of their music as well as the fact that the connections between the music of these Turkic groups fundamentally differ from their linguistic relations.

In the course of this enormous work a part of the musical map of this vast area stretching from China to Eastern Europe has been plotted. It is also a fact that no similarly extensive, analytic, comparative folk music research based on field work has been carried out earlier in Asian territories.

Summary of the research task

The long-term goal of my research is to systematize and compare by musical criteria the traditional songs of Turkic groups and other ethnicities living among and around them. I rarely touch on instrumental folk music, the repertoire of professional performers, the most recent strata, seldom or just occasionally discuss art music and the cultural, social, and anthropological implications of music are only sporadically considered, too: I concentrate on traditional folk songs.

There are close connections between the languages of Turkic groups, but their musical stocks are fundamentally different. That is not surprising, because these people are, at least in part, Turkified, and through their substrata they are in genetic and cultural relations with several non-Turkic peoples. My research therefore has repercussions; apart from the Turkic-speaking peoples tied by culture, language, and history, upon their neighbors and partly absorbed other peoples, creating the foundation for even broader future comparative ethnomusicological research of Eurasian groups.

This paper is aimed to provide a summary about the findings of my field research into the folk music of Anatolian Turk, Azeri, Karachay-Balkar (in Northern Caucasus and Turkey), south-western and Mongolian Kazakh, Turkmen, Uzbek, and Kyrgyz people between 1987 and 2019. In some articles I gave detailed account of the phases and results of collecting work, analysis, and comparative research.

Description of the performed tasks, methods of processing, sources

There were no systematized archives for the investigation of Azeri, Karachay-Balkar, Kyrgyz, Aday and Mongolian Kazakh, Turkmen, and Sufi Islamic music, while the Anatolian and Kazakh collections were hardly accessible. Besides, the material of the latter was poorly annotated; basic genres were missing, such as laments, lullabies, folk religious tunes. That was why I had to carry out extensive field work among several Turkic ethnic groups.

In the past 30 years I spent a total of some 10 years in areas populated by Turkic groups and collected and notated more than ten thousand tunes. I worked mostly in small villages and finished collecting among an ethnic group when the newly recorded tunes were already variants of former ones. The created Turkic archive belongs to the major systematized and elaborated collections of Azeri, Kyrgyz, Karachay and Turkmen folk music anywhere in the world. Concerning the degree of notation and analysis, the Anatolian and Kazakh sections are also important. This large number of tunes allowed us to draw unique and reliable conclusions, and the whole endeavor acquired the value of basic research.

The main groups of tunes I have collected since 1987 are the following: Turkish in Turkey (c. 4000 tunes), Azeri (600), Caucasian and Turkish Karachay-Balkar (1200), western and Mongolian Kazakh (600), Kyrgyz (1300), Turkmen (500), Sufi Islamic communities (700) and North American Indian (700). My investigations covered other non-Turkic peoples and religious communities of the area (1400 tunes). The entire collected material is summarized under “The archives” on my website.

The majority of collected tunes are videotaped, a considerable part of the collection has been digitalized; cataloguing and uploading them online are in process. I notated the Anatolian, Azeri, Karachay, Kazakh Kyrgyz and Turkmen tunes and presented large representative selections together with audio- and video-recordings in my books.

In addition to the works of Hungarian researchers in the Volga-Kama area and their followers some articles and even a few books have appeared on the folk music of some Turkic groups I studied thoroughly (Anatolian, Kazakh). In many cases, however, there are only tune selections (Azeri, Karachay, Kyrgyz) or not even that (Turkmen). I have studied the local and foreign folk music researchers’ works the great majority of which refrain from classification, let alone comparative examination. I touch on these in the discussion of the respective group of people. Let us mention some scholars who make at least partial attempts at comparison: Robert Lach, Béla Bartók, Viktor M. Beliaev, Viktor S. Vinogradov and Kurt Reinhard.

In my work I have applied the methods of comparative folk music research with great Hungarian traditions, of which László Dobszay wrote in one of his important articles. I resorted to the methods of ethnomusicology adapted to the currently predominant cultural-social anthropological trends in smaller communities such as the Sufi Takhtajis and the Alevi/Bektashi communities, as well as for in-depth research among the Aday and Mongolian Kazakh people. During fieldwork I did numberless interviews with musicians which are still to be processed.

I notated the collected tunes and classified them relying on the methods applied by my predecessors to the arrangement of Turkic folk music tunes. When comparing the material with Hungarian folk music, I primarily used Dobszay-Szendrei’s (1992) conception of styles.

The used symbols and the principles of transposition and musical systematization are described in the introduction of my books where I also explain why I could not choose strictly unified principles for the classification of the examined folk music materials. Let it suffice to note here that the significantly different musical materials required different criteria of classification. For instance, the Azeri, Turkmen, and Uzbek songs have short lines of a few neighboring tones as against broad-ranged four-lined pentatonic folksongs implying fifth-shifting. The main criterion of the systematization is first the melody line because the rest of the musical features (e.g., rhythmic scheme, syllable number, gamut, etc.) are less markedly characteristic of the tunes, and the grouping on their basis can easily be presented in tabular form.

The examined Turkic folk music stocks of the Anatolian Turkish, Sufi Turkish Bektashi of Thrace, Azeri, Turkmen, Uzbek and Tadjik, Karachay-Balkar, Kazakh and Kyrgyz relying on the material of my expeditions, as well as that of the Turkic groups in the region demarcated by the Volga, Kama, and Belaya, relying especially on the works of Lajos Vargyas and László Vikár (References).

Summary of the new scientific results

I can only list here some of the observations and findings about the folk music of different Turkic peoples and their relations to Hungarian music; these are expounded in more detail in the discussion of the music of individual groups in my books.

Of similar significance to the systematic collection of the enormous material is the analysis and classification of the musical repertoires, which provides a unique possibility for a musical review of the studied segments of folk music. The music classes can be study in details in my books (References).

Based on publications and collections by other scholars, I also reviewed the music of Turkic groups not mentioned analyzed here in details (e.g., Siberian Turk, Gagauz, Karaim, Crimean and Dobrudjan Tatar, Uzbek, Tadjik, Uyghur, and Yellow Uyghur groups) to which I make some reference at most; their inclusion into comparative research will be the task of a subsequent stage of research, or of a new generation of researchers.

There is little connection between the Turkic peoples’ linguistic and musical relations, probably owing to the different substrata. E.g., compared to the highly complex forms of Anatolian folk music the linguistically closely related Azeri folk music has just a few musical forms, and these have hardly any connection with the simpler forms of Anatolian folk music. Similarly, compared to the simple narrow-range diatonic tunes of southwestern Aday Kazakhs, the music of Mongolian Kazakhs living several thousand miles away from them is dominated by pentatonic tunes of passionately undulating melody lines, although the language of the two groups is practically identical.

Several complex Turkic folksong repertoires contain contradictory musical strata of different origins (e.g., Anatolian Turkish, Karachay, Kazakh and Kyrgyz), and at the same time, in the music of nearly every Turkic group the rate of one or two-lined simple forms is significant, and some repertoires are wholly traceable to these simple forms (e.g., Azeri, Turkmen).

Anatolia’s particularly complex and varied folk music is obviously largely a reflection of the ethnically mixed Byzantine area occupied by the Turks. This is the most complex of all Turkic song stocks, taking a distinguished place in the list of the world’s folk musics in terms of diversity. The songs of the linguistically closely connected Azeri, Uzbek and Turkmen people are predominantly simple, narrow-range tunes pointing to Iranian and in part Caucasian relations.

The music of Karachay-Balkar and Nogai people living on the northern slopes of the Caucasus is far more complex than that of the Southern Caucasian groups and it differs in its strata as well. In the former music there are several musical layers that can be found among neighboring Caucasian groups and were presumably borrowed by the Turkic groups from them. The music of the Azeris more to the south of the Caucasus displays strong Iranian influences (too).

Kyrgyz, and particularly Kazakh folk music is also complex, but it comprises different strata than the Anatolian music. The pentatonic strata of the equally diverse Uyghur and Yellow Uyghur folk music lead over to the musical realm of northern Turkic – Mongolian – Chinese music.

The zone of pentatonic Turkic music stretches from China through the Uyghurs, Mongolians, South Siberian Turkic groups, and the northern and eastern Kazakh areas to the Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir people in the Volga-Kama-Belaya area, and characterizes most of the old (and some newer) strata of Hungarian folk music. Among the northern and eastern Turkic groups only the music of the Yakuts (Sakhas) living scattered over an enormous area to which they arrived relatively late is not pentatonic. However, the Turkic tunes using pentatonic (and partially pentatonic) scales take a great variety of forms, and the different pentatonic scales are not represented with equal weight in the repertoires of different peoples, aptly illustrated by the common and different strata of e.g., the Cheremis, Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir, and Mongol folk music. The pentatonic phenomena of Russian, Finno-Ugrian and other peoples must be subject to a different research program.

The Turkic ethnic groups living more to the south have predominantly diatonic folk music of narrow-range simple melodies. Mainly in Anatolia and some central and southern Kazakh and partly Kyrgyz areas can one come across more complex, non-pentatonic tune forms. In harmony with that, the use of micro tones is more frequent in the southern Turkic areas (Anatolian Turkish, Azeri, Turkmen, Uzbek music), being less dominant in the middle strip of the territory (Karachay-Balkar, Kyrgyz, Kazakh areas) and is negligibly rare in the pentatonic belt. Within diatonic scales, the minor character scales are overrepresented among the studied groups, while scales with the major third (mostly of Major or Mixolydian character) are found among the Karachay-Balkar and Kyrgyz people in greater proportions.

Despite major differences among individual Turkic folk music repertoires, some common musical traits and even musical strata can be observed. In an article I compared the fifth-shifting tunes of Turkic groups around the Volga-Kama-Belaya and of other Turkic peoples, Hungarians, and Mongolians, and also outlined the Turkic background of the Hungarian (and international) lament style, psalmodic, descending pentatonic and fifth-shifting tunes as well as songs of children’s games. By way of an example, I mention the narrow-range simple-form Phrygian tune group of two short lines, which do not coalesce into a massive stratum in Hungarian folk music but are saliently important in Anatolian, and particularly in Azeri, Turkmen, Uzbek and Aday Kazakh folk music.

Grouping of Turkic folk music stocks, Hungarian connections, and the situation of comparative research

Before presenting the summary tables let me repeat that repertoire of Turkic folk music are often related to the music of neighboring groups and people they have integrated. In the south there are strong Iranian contacts (Azeri, Anatolian, Turkmen, Uzbek), in the north and east relations to the more broadly arched pentatonic music of the Mongols can be gleaned (Mongolian and eastern-northern Kazakhs, some Siberian Turks, Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir), while in the region of the Caucasus musical fusion with the Cherkes, Kabard, Alan and other Caucasian peoples can be observed (Karachay-Balkar, Nogai). The music of Turkey (also) mirrors the culture of absorbed and Turkified substrata to a great extent, the music of Siberian Turkic groups is basically pentatonic but their music so fundamentally differing from the pentatonic forms of the Mongolia – Volga-Kama area requires further thorough comparative investigations. The motivic organization in the music of the Yakuts, who migrated to their current area later, also needs further studies as this music differs from the other Turkic repertoires and has forms that are like the motivic music of some Finno-Ugrian groups living at the Volga-Kama area).

Table 1 gives a grouping of Turkic folk music stocks I have overviewed. Group 1 includes the Anatolian Turks with their highly complex and basically diatonic music, showing only some pentatonic traces. Group 2 includes the Azeris who are closely tied to Caucasian and Iranian traditions, and the Turkmens with strong Iranian musical impacts. The folk songs of these people consist of very simple melodies moving on a trichord or a tetrachord. In Group 3 the Uzbeks with strong ties to the Iranian Tadjiks can be seen as a separate entity, though their songs show some similarities to the simple melody styles of the Azeris and Turkmens. In Group 4 there are the Karachay, Nogai and Kumuk people. With their composite and convex melody repertoire these folk musics, on the one hand, interacts with that of the neighboring (non-Turkic) Kabard people, and on the other hand with some important musical layers of the southern and western Kazakhs, Anatolian Turks and Kyrgyzs living far from them. Group 5 comprises the northern Turkic groups with dominantly pentatonic music: Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir, some Altay Turk, Oirat and Tuvan people, with close relation to the pentatonic practice of Mongols and Buryats. Group 6 includes the Kazakhs living over a vast territory with their highly compound folk music displaying ties toward the diatonic music of the south and the pentatonic styles of the Turkic east. Group 7 includes the Kyrgyz, Khakas and several Altay tribes. Despite to their common nomadic background the music of groups 6 and 7 shows remarkably differences.

|

|

|

● 5. Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir, some Altay |

|

|

|

|

● 4. Karachay,

|

|

|

|

|

● 1. Anatolian |

● 2. Azeri (~Caucasus) |

● 3. Uzbek |

● 6. Kazakh |

● 7. Kyrgyz, Khakas |

Table 2 illustrates that in the music of which examined Turkic repertoire certain old Hungarian folk music styles can also be demonstrated. This is discussed in detail in different chapters of my books and in the books of László Vikár.

|

Hungarian folk music form/style |

similar Turkic forms |

|

small form of lament |

Anatolian Turk, Azeri and Kyrgyz; to lesser extent: Karachay-Balkar, Turkmen, Aday Kazakh and Tuvan |

|

pentatonic descending tunes, including fourth- and fifth-shifts |

Volga–Kama–Belaya-region (Chuvash, Cheremis, Tatar), Mongol, Uyghur, Yellow Uyghur; to lesser extent: Karachay-Balkar |

|

psalmodic tunes |

Anatolian Turkish, Aday Kazakh, Karachay-Balkar, Caucasian Avar |

|

tunes built of twin-bar motifs rotating around the middle note of a trichord |

Anatolian Turkish; to lesser extent: Karachay-Balkar. This type can be found Azeri dance tunes too. |

|

’regös’ (minstrel) tune |

Karachay-Balkar |

|

returning (domed) structure |

Karachay-Balkar, Kyrgyz, Anatolian Turkish and Kazakh. This form seems to be a newer development in Turkic music. |

Table 3 is meant to demonstrate the situation of Turkic folk music research did by Hungarian scholars. Thanks partly to Hungarian researchers; we have a relatively clear picture of Oghuz, Kipchak and Chuvash folk music. That is promising because considering their numeric rate, state-creating ability, and the size of the area they populate, these ethnic groups comprise the bulk of the Turkic-speaking populace. In the table, I indicate my collections in normal bold type, Vikár-Bereczki’s collections in italicized bold type, and the groups whose music has not been included in the comparative research yet are put in parentheses.

|

|

language group |

location |

|

|

I.1 |

Oghuz |

south-west |

Turkish, Azerbaijani, Turkmen, (Gagauz) |

|

I.2 |

Kipchak |

north-west |

Kyrgyz, Kazakh, Karachay, Balkar, Bashkir, Kazan Tatar, (Crimean Tatar, Karaim, Karakalpak, Nogai, Kumyk) |

|

I.3 |

Turkestani |

east |

Uzbek, (Yellow Uyghur, modern Uyghur, Salar) |

|

I.4 |

Siberian |

north |

(Siberian Tatar, Altay, Shor, Chulim and Abakan Tatar, Khakas, Tuvan, Karagas or Tofa) |

|

I.5 |

Khalaj |

|

|

|

I.6 |

Yakut |

north |

(Yakut) |

|

II. |

Bulgar-Turkic branch |

Volga-Kama area |

Chuvash |

Of course we know that the ethnogenesis of Turkic peoples seldom has been a tidy process. Many of theem have multiple points of origin, with ethnie layer placed on top of ethnie layer. Athough there are many ancestral elements shared in common by a number of Turkic peoples (e.g., Kipchak elements found among among the Uzbeks, Kazaks, Kyrgyzs, Karakalpaqs, Nogais, Bashkirs etc.), the proportions of the common elements entering each varied. Moreover, some of the shared elements (e.g., the Kipchak) were themselves hardly homogeneous. In addition, many bad or developed unique combinations of elements which helped to distinguish one from the other.

Besides folk music research, as part of the social sciences, cannot propose finite, petrified theories, and research into the music of Turkic ethnicities is far from being completed. Not only are entire ethnic groups missing, but several tasks are still to be done concerning the already studied musical stocks as well.

Collecting work must go on, the relics of traditional tunes and the contemporary repertoire must be surveyed. It is important to create large, well-documented, accessible (online) digitalized archives; to monographically elaborate the music of certain regions and ethnic groups; to carry out the comparative analysis of the tune stock of Islamic folk religion, among many other tasks. It remains for future research to involve the folk music of Turkestani and Siberian Turkic groups, of smaller Khalaj and Yakut communities, and to continue the Kazakh and Anatolian research. Most of these tasks await local colleagues and international work teams such as the Music of the Turkic-speaking World ICTM Study Group I founded.

Despite the many tasks ahead of us, I hope that proceeding along the path signposted by our great predecessors; our results in the collection and comparative analysis of the folk music of this enormous area have contributed to its better understanding. I also hope my investigations will be of help to the practitioners of comparative folk music research and ethnomusicologists adopting the methods of cultural anthropology alike, so that the foundations of an even broader comparative musical research of Eurasia involving even more ethnic groups shall be firmly laid. The review of the folk music of the vast Eurasian territory may also provide data for the confirmation or, conversely, the modification or reconsideration of some results of the prehistory of Hungarian folk music. Finally, a classified, systematized folk music material may help music education, and a large folk music database provides the possibility to illustrate the musical culture of the peoples concerned.

About the Folksongs of Some Turkic People

Let us now survey the main musical styles of some Turkic groups, trying to find out what characterizes only a few or a single people, and what can be explained within a ‘stylistic community’. Here, I cannot embark on the description of each folk music style, but I assess the most important folk music layers to try and define the mutual places of the Turkic folk music repertoires with a glimpse of the music of some non-Turkic neighbors.

Anatolian Turks

The population of nearly 80 million people living in the area is highly complex, and hence their folk music culture is also varied. Apart from diverse groups of Turks and Turkified people, there are Kurds, Laz, Greek, Azeri, and several other ethnic minorities. Many kinds of musical forms crop up ranging from motifs moving on a few notes to descending four-lined structures spanning two octaves. Great differences can be discerned by geographic regions and genres, too: while the folksongs of the Sufi Takhtajis in the Taurus Mountains belong to a single melody group, their religious repertoire includes several fundamentally different forms. Despite that, a survey of Anatolian folk music is not hopeless. Béla Bartók tried in 1936, and I have surveyed a far larger material myself, too (Sipos 1994, 1995, 1997, 1997).

There are strong musical connections between the Hungarian and Anatolian psalmodic style, the lament style and the tunes of children’s games. Hungarian research derives the psalmodic tunes from European origins, the tunes of the small form of the lament style are thought to be a Finno-Ugrian legacy, and the children’s game songs of mi-re-do notes rotating around the middle note are known to arise among most diverse ethnic groups independently of each other. My recent investigations tend to suggest that the Anatolian tune types should be conceived as the heritage of the basic Byzantine population tinted with Turkic and other influences. It is an important difference that as compared to several Hungarian musical strata, the Anatolian music is essentially and almost exclusively diatonic.

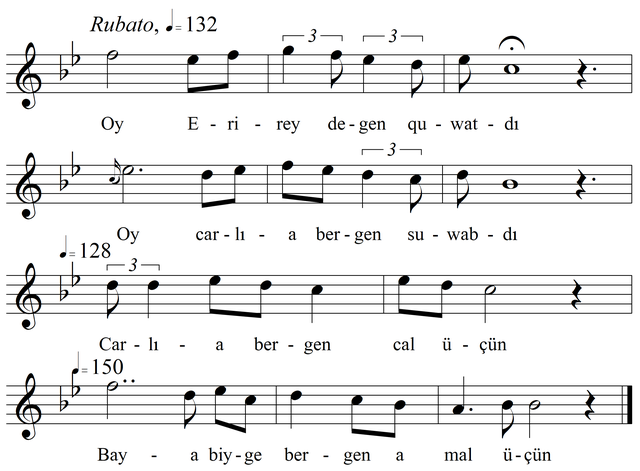

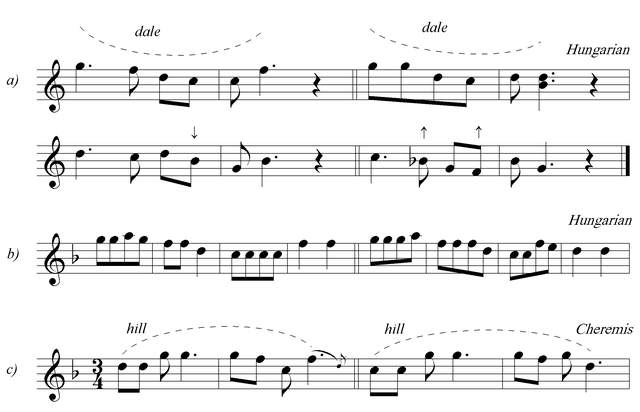

In addition to diatony, an important feature is the conjunct motion of the melody which develops along neighboring notes and the first half of the tune does not get separated from the second in terms of pitch zone. Despite its variety, these features lend some homogeneity to the great part of the repertoire of the Anatolian region. A disjunct structure, “small fifth-shifting” or fifth-shifting only occur sporadically, almost by accident only between the lines within the overall descending tendency. A typical feature is the sequencing of lines or bars in several tunes, and even styles (Example 1). There are hardly any tunes of architectonic structure, and if there are some, they are far less developed than their Hungarian counterparts.

Typical of Anatolia is the diversity of asymmetric rhythms whose ancient European (Greek) origin is alluded by to their primary (but not exclusive) presence along the seashores once populated by the earlier Greek city states and their environs. A few asymmetric rhythmic schemes also occur in the music of the Turkmen tribes of the Taurus Mountains, as well as among Turkmens, Uzbeks, Uyghurs, but are missing from the folksongs of other Turkic groups except for the repertoire of some bards.

The tunes are performed in both free and strict manners, their construction is basically authentic, the last note most often being the lowest pitch as well. Most songs is 2-lined or 4-lined or derives from these formulae. Scales with the minor third are predominant, but degrees 2 and 6 are more unstable than the rest, intoned somewhere between the minor and major third and sixth, resp. degree 2 is practically never absent, while degree 6 is often missing from the scale.

In Anatolian folk music there are numberless Aeolian tri-/tetrachords and even bichord tunes—the bulk of them are one-lined or two-lined in accord with the small compass. There is a considerable number of minor (and major) pentachord tunes, several of which have analogies in Hungarian folk music (Example 2).

The compass of the Turkic tunes does not exceed seven notes (1-7), except for some South Turkish uzun hava tunes. Contrary to a generally held view, the scales with augmented seconds are rare and the augmented interval is usually between notes 2 and 3, sometimes falling just narrow of a real augmentation.

It is impossible to survey the whole repertoire of Anatolia in a few pages, but in my books, I introduced the central tunes of the main tune classes from two angles. First, I ranged them in tune groups according to cadence, length and number of lines, and the height of the first line; then I rallied the groups of similar melody motion along one long or two shorter melody lines (or two long and four shorter lines) into respective classes and demonstrated the interrelations of the classes in tables. The tables clearly illustrate which tune classes are preponderant, which are rare or missing. I also demonstrated the present the central tunes of the tune classes starting with the twin-bar forms, followed by those retraceable to one long (or two short) lines and finally those that can be traced to two long (or four short) lines. However, the detailed elaboration, comparative analysis, and historical exploration of the musical strata of the folk music of this enormous area with a population of some 80 million are still awaiting the work of contemporary and future generations of folk music researchers.

Bektashis of Thrace

I conducted a separate research among a Sufi Turkish group, the Bektashis of Thrace. They are a mystic community of Islam living in the European part of Turkey, migrating here from Bulgaria, and thus knowledge of their music allows an insight into the folksongs of both the Bulgar Turks and a Sufi religious society.

There is much concordance between the Bektashi and the typical Anatolian tunes. Bulky layers are constituted by the mi-re-do-core tunes rotating around their middle note, by diverse forms of the psalmodic style and by the sequentially descending tunes (Example 3). Not infrequently, a lengthier tune is built from a single or just two different motifs.

b) diverse form of the psalmodic style and c) sequentially descending tunes

Typical is the conjunct motion and form with descending melodies in lines of convex or descending shape. This applies both to tunes built of variants of a single short hill-shaped la-re-(mi-re)-do-(b)si-la line and to forms of many lines.

In the first line of several Bektashi tunes there is a rise-fall-rise undulation over a narrow tonal range; this is less frequent in Anatolia but can be found as typical in several Turkic groups, e.g., the jir tunes of the Karachays, among Kyrgyz, Aday Kazakh and particularly Mongolian Kazakh people, often with a wider compass, too (Example 4).

There are disjunct structures as well, but never in pure form. The domed, returning construction is more frequent than in Anatolia; detailed analysis has found these tunes to be specific to the Bektashi community, mainly belonging to their religious repertoire.

Apart from the sol’-mi-re-do-(b)si-la scale, incomplete scales are rare; most interestingly, one is the re-si-la tritonic scale of laments and bride’s farewell songs. The small form of the Hungarian and Anatolian lament is not found here.

As is typical of folk religious tunes in general, there is a close connection between Bektashi religious and folk songs. The simplest, single-line small-compass forms dominate folksongs and some religious semah dance tunes, and the wider the compass and the closer we come to four-lined structures, the greater the number of similar religious and folk tunes.

Azeris

Progressing eastward from Anatolia, one finds the closest language relatives of the Anatolian Turks, the Azeris. The area of Azerbaijan was Turkified by the same Turkmen tribes as Anatolia, but the substratum upon which they settled was different. That must be the reason why the two folk music stocks are so dissimilar. In Azeri areas the surviving of the music of a complex Caucasian and probably an even more significant Iranian basic layer can be found.

Compared to the highly complex Anatolian folk music, Azeri folk music in the country and beyond, in areas of historical Azerbaijan now in Iran, is rather simple. Melody motion is conjunct; scales with large leaps, melodies rotating around a central core, a starting ascent or tunes retraceable to a single motif or twin bar are very rare. The latter form appears at most in instrumental music.

The typically single-core or two-core Azeri tunes move in trichords, tetrachords or even bichords of Aeolian, Dorian or Phrygian/Locrian coloration, comprise 7-syllabic, 8-syllabic or less frequently 11-syllabic descending or convex lines rarely arranged into strophes. They are performed in 6/8, 2/4 or other meters based on these, in tempo giusto, rubato or parlando manner (Sipos, 2004, 2005, 2009). Longer lines and/or fixed four-lined structures only sporadically occur here.

It well illustrates the simplicity of the Azeri musical realms that the semi-professional Azeri ashiks only use the simple forms of Azeri folk music, unlike the Turkish or Turkmen bahshis (bards). More complex forms can only be found in instrumental dance music and in the courtly mugam/makam music.

The musical realm of the Azeri tunes is characterized by a plenitude of variations on the basic forms despite the great degree of simplicity.

Let me call attention to three Azeri tune groups. The tunes of one move on the notes of the (sol’-fa)-mi-re-do chords, are performed parlando, their lines end on re or do—thereby resembling the small form of the Hungarian and Anatolian laments. The weight of the analogy is further enhanced by the genre of the tunes being laments in most cases (Example 5).

(The audio examples are only similar to the notated melodies)

However, this tune type is only a subtype of major character of the Azeri laments which have three modal variants. Another group contains four-lined Aeolian tunes which fit into several Turkic and non-Turkic psalmodic styles. And a few melodies of this group have considerable Turkic and Hungarian backgrounds. However, I only met with such tunes in publications and only found similar tunes among the Avars living in Azeri areas during my field-research. Four-lined constructions are basically rare in Azeri areas, whereas, at least today, they are prevalent in the Hungarian material and characterize at least half the tunes of other Turkic (Anatolian, Karachay, Kyrgyz, Tatar, etc.) groups.

Phrygian/Locrian tune groups built of one or two short narrow-ranged lines acquired greater significance after the analysis of Turkmen (and Tajik) folk music.

The folk music of a few minorities living in Azeri territory is also revealing. I collected music among Avars, Tats, Zakhurs, mountain Jews, Russians and Hemsilli Turks. The Tats of southern Iranian origin and the Zakhurs of Caucasian roots largely merged with the Azeris, and the tunes of the basic strata of the Mountain Jews’ music who fled here from the eastern Caucasus are also practically indistinguishable from the Azeri tunes.

Different is the case of the Avar, Russian and Hemsilli Turkic songs. The Avars constitute the largest and most advanced ethnic group of Dagestan, a part of whom live in today’s Azerbaijan. Unlike the rest of the minorities there, they preserve their culture, and a great part of their songs are different from the Azeri tunes. Typically enough, about half the Avar tunes I collected more or less fits the psalmodic style. The re-do-la triton of the recorded Russian tunes was really refreshing in the consistently diatonic world.

The Hemsilli Turks migrated here from Georgia; most of their tunes are in accord with the basic layers of Azeri and Anatolian folk music, including the small form of the lament style and even a few tune variants of the psalmodic style. They have a few tunes that cannot be found either in Azeri or in Anatolian folk music.

Let us sum up at this point the Hungarian and Turkic relations of Azeri folk music. It immediately strikes the eye that compared to the seemingly homogeneous Azeri tune stock of a few elementary styles, the folk music of several (but not all) Turkic groups and the Hungarians contains many essentially different tune layers. One can find analogies to most Azeri tunes in Anatolia, the most convincing parallels coming from northern Anatolia where the rate of Kurds and Azeris is high. Unlike Hungarian and Anatolian folk music, Azeri tunes are predominated by narrow tonal ranges and the rarity of fixed four-part constructions. Besides, melodies built of trichord or tetrachord motifs rotating around the middle note are only found among instrumental tunes—and infrequently, too. What there is a profusion of in Azeri folk music are the tunes similar to the small form of Hungarian and Anatolian laments. This is perhaps the only folk music form that displays real similarities between Hungarian and Azeri music.

Owing to the absence of pentatony and large tune forms, the diatonic and narrow-compass Azeri tunes have nothing to do with the pentatonic musical layers of Tatars, Bashkirs and Chuvash people living in the region of the Volga, Kama, and Belaya. The music of the eastern Chuvash minority and the Christian Tatars includes some narrow-range motivic forms, but they are almost always tritonic or tetratonic tunes containing leaps. In this region, the Mordvin and Votyak folk music contains a few do-re-mi-re-do 3-4-note single-motif hill-shaped lines, but their character is different from the Ionian trichord Azeri tunes.

Since the forbidding mountain range of the Caucasus separates the ethnicities living on either side of it, it is not surprising that the varied folk music of the Karachays and Balkars speaking a Kipchak Turkic tongue hardly have any similar layers to Azeri music.

A bit different is the case of the Mangyshlak Kazakhs on the other side of the Caspian Sea, as they are separated by a sea, and not a mountain range from the Azeris. The central lament stratum of these Aday Kazakhs move on the same Phrygian/Locrian chords—though with a somewhat different logic—as one of the most characteristic tune groups of the Azeris. The Kazakhs of Mangyshlak have far more colorful and numerous musical styles than the Azeris, but their musical styles substantially deviate from the pentatonic musical styles of the Kazakhs in Mongolia more to the east. By contrast, a great part of the Turkmen and Uzbek (as well as Tajik) folksongs—as will be seen—display strong stylistic similarities to the central Azeri folksong types.

Turkmens

Let now us see the folk music of Turkmens on the opposite side of the Caspian Sea, across from Azerbaijan. In the ethnogenesis of the Turkmens, a considerable Iranian population took part in addition to Oghuz and Kipchak tribes, which put a deep imprint on their folk music, too.

The melody contour of Turkmen folksongs is just as simple and homogeneous as that of the Azeri tunes, verified by all available publications and my collection of 600 tunes, too. In other aspects, however, they display a rich variety, e.g., in the women’s performing style, in peculiar timbres, the use of quarter tones and special micro rhythms, etc. It is quite clear that their repertoire fully satisfies the musical needs of the community. The copious use of micro tones is more an Iranian than a Turkic heritage, also reinforcing the massive Iranian substrata of Turkmen music.

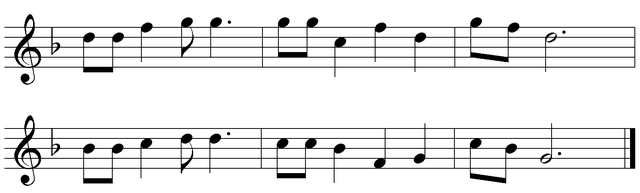

Turkmen folksongs have narrow compass, move fast, the melody line often descends from the highest to the lowest pitch, and the forms are very simple. Most tunes have two lines, and a considerable portion of the four-lined songs can be directly tied to two-lined versions (Example 6).

Some tunes recite one or two notes, but the compass of their more melodious pieces does not go beyond a trichord or tetrachord, either. They may have minor or Phrygian character or between the two using micro tones. These tunes are characterized by short lines, simple rhythmic formulae, and a descending melody outline. The only popular structuring principle is the descent of motifs in second sequences, which is also frequent in the folk music of Anatolia, but from the equally simple music of Azerbaijan it is almost wholly missing. Compared to Azeri music, Turkmen tunes are often in 5/8 meter. Despite the four-lined text stanzas, one-part or two-part half melodies are most frequent; a melody structure of four different lines is rare.

Comparison of the Azeri and Turkmen Repertoires

The simplest tunes are sung by women in both ethnic groups. By contrast, the (semi)professional singers—Turkmen bahshi, Azeri ashik—and the paid singers of weddings are mostly men.

The folksongs, ritual songs and Islamic religious tunes of both groups are simple, in 2/4 or 6/8 time, often performed rubato (sometimes parlando). Melody lines are 7-syllabic or 8-syllabic, the overall form can usually be derived from one or two lines, the compass rarely goes beyond the fourth, and tunes moving on two neighboring notes are not infrequent. Though accurate intonation is not characteristic of Azeri tunes, in Turkmen folksongs the role of quarter tones is far stronger. In both groups’ music the typical rhyme scheme is a a b a, and refrains are rare.

Nearly every Azeri tune type has its Turkmen parallel and vice versa. A major difference is that in Turkmen folk music there are considerably fewer tunes moving on Ionian tri-/tetrachords.

The Phrygian (sometimes Locrian) tri-/tetrachord plays an important role in both folk music. Similar simple Phrygian tunes are frequent among the Uzbeks, Tajiks and in Anatolia, too. In Sipos (2004, 106-115) several Azeri-Anatolian parallels are presented.

The repertoire of Azeri ashiks consists mainly of folksongs (Sipos, 2004, 116-118). In the introductory section of their performance Turkmen bahshis also sing simple tunes which, however, often have longer lines than the folksongs and gradually evolve into broader-compass intricately structured compositions. Another difference is that the Azeri ashik’s instrument is the three-stringed baglama well-known in Turkey, while the Turkmen ashik prefers the two-stringed dutar. Both ashiks and bahshis may sing solo, may accompany their singing with an instrument and may also have a small ensemble. The instruments of an Azeri ashik’s ensemble include the baglama to accompany his singing and play interludes, zurna (sometimes zurnas) and a drum. In a Turkmen bahshi’s ensemble there are one or two dutars (plucked lute) and a gijak. Complemented with the blown balaban and a drum, the latter becomes the typical apparatus of Azeri court musical mugam (maqam) performance.

The vocal pieces of Turkmen bahshis are characterized by two basic tune types: (1) narrow-ranged low-register tunes in giusto rhythm similar to folksongs, and (2) more complex tunes in a higher register. The complex forms are sometimes introduced by simple forms that can be derived from or are identical with the second half of 4-lined tunes. With the addition of refrains, the strophic structure can be enormously enlarged.

In the repertoire of Turkmen bahshis many popular Anatolian uzun hava tunes have analogies. The corresponding Turkmen tunes are heavily varied, so much so that sometimes only a tune variant of the performed cycle can be regarded as a parallel to the Anatolian tune. Besides, the cadential notes are far more blurred in the performance of a Turkmen bahshi than in Anatolia.

Both long—often additionally extended—lines of many bahshi tunes descend from high: the first line to degrees 3-4, the second to the tonic note. This scheme is frequent in the Anatolian uzun hava tunes, including the ones called türkmeni around Adana, though the latter often start the descent even higher, from degrees 10-11.

While further analyses of Turkmen folksong cannot have too much surprise in store, the deeper investigation, and analyses of the less studied and constantly changing Turkmen bahshi repertoire should be high on the agenda of folk music research.

Uzbeks (and Tajiks)

The neighbors of Turkmens are the Uzbeks, east of whom live the Tajik and Kyrgyz people. The Uzbeks speak a Turkic language, the Tajiks speak an Iranian tongue, but the two groups often lived and still live side by side on the same territory and the majority of the population speaks both languages. The music of the two groups is based on similar melodic, modal, and rhythmic foundations, many tunes having both Tajik and Uzbek texts.

Uzbek music preserves several forms that can be found among other Turkic musical stocks more to the south, whose melody line comprises both a rotation around the middle note of a trichord and the ascending or convex melody shape where Anatolian (Sipos 1994: No 45, 49) and Azeri (Sipos 2004, No 318) analogies can also be shown. Because of its improvisatory performance, scale, melody progression and cadences the Uzbek lament reminds one of the bi-cadential Hungarian and Anatolian major hexachord laments, and some laments are even analogous with the Hungarian two-lined lament scheme of minor character.

Several Uzbek laments move on the re-do-la tri-tetraton. Such tunes built of motifs are also frequent in the essentially non-pentatonic Kyrgyz (Sipos 2014), Anatolian (Sipos 1995: 79-80), and this is less surprising Hungarian music having pentatonic layers (Vargyas 2005: 0148) and in wholly pentatonic Chuvash and Tatar folk music (Vikár 1993: 107-108).

The rhymes of the Uzbek spring rain magic is recited rhythmically on varied forms of the do-do-do-do | re-sol sol motif, but not always on precisely intoned pitches. Motifs and tunes built on the re-do-sol triton can be met with in the musical repertoires of several Turkic groups, but they are rare as independent motifs in Hungarian folk music. Together with the tune on the re-do-la core these tunes allude to an ancient, pre-pentatony layer of this folk music.

There are two basic melody contours in Uzbek and Tajik folk music: (1) after a jump from the tonic to the highest degree of the scale at the beginning, the melody descends; (2) the melody traces a rising-falling outline. Less frequently undulating motion can also be found. Both melody contours can be found in simpler and more complex tunes.

Simple narrow-compass one-lined or two-lined Phrygian tunes are frequent. As already discussed at several loci, this form together with other simpler forms described in detail in Sipos (2004), presumably represents an Iranian substratum of Turkic folk music. It is also confirmed by its popularity in Uzbek and Tajik folk music.

Four-lined forms are rarer. In the discussed territory a special form of psalmodic tunes can also be spotted but only among the Tajiks and only sporadically. The melody progression of some Tajik melodies is like a few psalmodic tunes with the difference that lines 2 and 3 end on degree 2 instead of b3. Such tunes are found in the music of other (e.g., Anatolian Turkic, Kyrgyz, and Karachay) groups but they hardly ever occur in Hungarian folk music. Example 7 would pass for a Hungarian psalmodic tune, were its main cadence b3. In Tajik folk music a few disjunct structures can also be rarely found.

Karachay-Balkars

After the Azeri, Turkmen, Uzbek (and Tajik) groups using simple forms, let us move back westward, to the Karachay-Balkars geographically close to the Azeris but separated from them by the impassable Caucasus Mountains. The northern slopes of the Caucasus Mountains are important for Hungarian ethnogenesis and for many Turkic groups: this is where the steppe narrows and where the groups proceeded westward during the great migrations of the Avars, Huns, or, for that matter, land taking Hungarians.

Though less varied or rich than Anatolian folk music, Karachay music contains several different musical forms many of which have Hungarian connections. In their folk music simpler songs are underrepresented and there are many complex 4-lined forms. They have a tune class of very specific textual subdivision called jir which they regard as a typically Karachay form specific to them. However, such tunes can equally—and even more numerously—be found in the music of the Kabards, and since the form of jir tunes is so alien to Turkic music, it is justified to regard them as borrowings from the Kabards.

The typical Karachay tunes trace a descent or a hill-shaped curve in each line, and there is conjunct motion within a line stepping on neighboring notes without large leaps and without going under the cadence note. The overall form is also descending, each consecutive line moving in a bit lower zone. At the same time, it is not infrequent to have an upward leap from the fundamental note or its vicinity at the beginning of the first line, and sometimes there is some up-and-down stepping in the form of rotating around a middle note.

In the contemporary Karachay musical realm tunes built of short motifs are rare. They include the tune bouncing up and down on the fifth, and some rain incantations rotating around the mid-note of the mi-re-do trichord. The latter is a central form of Hungarian, Anatolian and Karachay children’s songs and is one of the main types of rain-making incantations. Similarly, to Azeris, Turks and Kazakhs, some tunes of the Quran recitation also rotate on the mi-re-do trichord and end on re.

Karachay folk music also contains plagal tunes with falling-rising melody contour. Such are the Hungarian regös tunes whose origins and relations have been moot questions of folk music research since the turn of the 20th century. Many regards them as vestiges of shaman rituals which incorporated Byzantine, Slavic and Caucasian influences still before the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin. At any rate, this kind of tunes (like the regös tunes in Hungarian music) are alien in Karachay folk music, but their texts—just like those of the Hungarian counterparts—allude to very ancient traditions; the genres of several pertinent songs are rain magic, lullaby, or tune of some archaic religion (Example 8).

The opposite of the typical hill-shaped or descending line forms is the concave, valley-shaped line or a line sinking to the fundamental note in mid-line. Sometimes one finds an ascending first line, too. About 10% of the presented tunes have descending or concave first lines, so these tunes are not exceptional in the Karachay musical realm, even if in the collected material their rate is lower. What is truly rare is an upward jump after a lengthier stay on lower notes, and also rare is a melody progressing on the notes of a broken chord. A line-ending leap from degree VII to b3 can sometimes be met with, and a jump down to degree V in some archaic tripodic tunes is also possible. In a few bars of several tunes there are larger skips, which deviate from the general conjunct melody progression of Karachay music.

Many Karachay tunes consist of one or two short lines and their variants. Line variants end on the same note as the preceding line, but each subsequent line moves within a narrower compass. Descending and hill-shaped, convex lines are frequent. Nearly every southern Turkic group has such melody patterns among their tunes. Owing to descent and convex line shape, grouping by cadence is satisfactory; I discuss the Karachay tunes of major and minor characters together. It well describes the structural development of Karachay folk music that even its most elementary tunes become arranged into four-line forms. The main cadence is most often (1), (2)—of lament character, or (b3) or rarer (4) or (5), the latter mainly in religious zikr tunes.

With their free performance, improvisatory treatment of the lines and descending melody contour some of the two-core Karachay tunes of major character with (2) main cadence do conjure up the realm of Hungarian, Anatolian and Azeri laments. The type that descends on a major hexachord, cadences on re and do is part of a broader musical style of rubato performance in Karachay (and Kabard) folk music including heroic songs. Similarly, to the downward extension of the end of some Hungarian laments, the melody may be enlarged, the line sequences may be enlarged in (la’-sol’)-fa-re-do › (si)-sol direction, too.

Undulation is characteristic of the lines of several tripodic tunes with (b3), (4) or (5) main cadences—this melody motion has already been seen in the music of several discussed Turkic groups.

The overwhelming majority of tunes in today’s Karachay music has four-lined forms. Below I touch on some of the most important groups.

Four Short or Tripodic Lines With (2) and (b3) Main Cadences

They descend evenly on minor character scales, from a typically higher starting line, medium-range middle lines and a lower fourth line. This summary description applies to two different subgroups. The lines of one descend with second sequences—these are apparently more recent tunes. The other very popular form has a more symmetrical, more dignified structure, its general description satisfying the criteria of the psalmodic style of Hungarian and many other ethnic folk music. A part of the Karachay psalmodic tunes are religious (zikr) tunes, but there are several lullabies, which suggests that the form is more archaic and was later incorporated in the religious repertoire. There are tunes of similar melody progression, but their main cadence is (2).

Four Short Lines With (4/5) Main Cadences and a Higher Beginning

In accord with the broader compass the melody outline is descending and sometimes exact or partial fourth-shifting and fifth-shifting can emerge, but a descent on second sequences is not exceptional, either (Example 9). The series of cadences aptly characterize the tune groups: 5(4)x, 4(5)x, 5(5)x, 6(5)4/5, 8(4)x and 7(5)b3.

Four Short Lines With (7/8) Main Cadences

The main lineament of these tunes is that their first line moving basically on degrees 7-8 may rise as high as the tenth degree and end high, on degrees 7, 8 or 9. The typical cadential series are 5 (7/8) 5 and 7/8 (7/8).

There are four-lined pseudo-domed (AB/AvarC) and domed Karachay tunes of four short lines, too. These, however, do not echo the returning structure of the Hungarian new style because lines one and three are identical or at least similar and their second line is also low. Many signs indicate that these tunes belong to a more archaic style. Some small-domed tunes have their first and fourth lines run low and the interim lines a bit higher; these also deviate from the majority of Karachay tunes.

At last, I mention a few Karachay tunes with four long lines and returning structure, in which the inner lines are a fourth or fifth higher than the outer ones. These appear to be of a more recent style and display strong similarity to some Hungarian new style tunes.

Karachay-Balkar jir Tunes

At the beginning of my field research, I took note of a peculiar tune type whose variants were found later, too, at every collection site. I gave a detailed account of them, so let it suffice here to repeat that most probably the jir style is a borrowing from the neighboring Adyghe people among whom it enjoys extraordinary popularity while no trace of it can be found among other Turkic groups.

In sum, within a broad stylistic similarity, more concrete likenesses can be discovered between Karachay and Hungarian children’s songs. A part of the Karachay-Balkar psalmodic, descending and lament tunes probably belong to the same primeval “stylistic species”—to use Bartók’s term—as the corresponding Hungarian, Anatolian, even Bulgarian, Slovakian, Romanian and some other ethnic tunes. Aside from characteristic ethnic and areal differences, the overall stylistic similarity, the closeness of individual phenomena, the melody writing, etc. urge for the continuation of research into the common origin or at least the close musical connections of these musical repertoires. A lot of Karachay tunes have convincing or more distant Hungarian analogies and historical sources permit the assumption that there might be genetic relationship between certain layers of Hungarian and Karachay folk music. At any rate, it can be declared that after Anatolian folk music it is Karachay music that displays the closest similarity to the more archaic and non-pentatonic layers of Hungarian folk music.

To be able to draw further conclusions, we should get a deeper insight into the folk music of the neighbors of the Karachays, the Osetians, Kabards and Cherkesses, which contains several similar strata to Karachay-Balkar music. One can find Kabard parallels to several tunes or even groups of the most important and most widespread Karachay-Balkar tune class, jir. The Karachay research has confirmed that the music of an individual ethnic group cannot be studied separately; the comparative examination of the culture of peoples living on wide contiguous areas is indispensable.

Kazakhs

In the area of Kazakhstan equal in size to Europe several musical researches have been conducted, but no synthesis has been completed or thorough analytic descriptions written. Beliaev (1975: 77-78) summary statement is that the Kazakh tune types rest on a common national foundation and are special realizations of the Kazakh national melody character, but Slobin (Beliaev 1975: 123) disagrees. In general, it can be stated that in addition to the regional styles, there is a great variety of tunes, a wealth of expressive details and a close connection with live speech in many Kazakh areas.

I have compared the folk music of the southwestern Aday Kazakhs and the Mongolian Kazakhs. It has turned out that despite the near-identity of their tongues, the Aday tunes move in narrow ranges along diatonic scales, as against the wide-compass pentatonic folksongs of passionate undulation among the Mongolian Kazakhs, while the latter do not resemble the pentatonic tunes of the Mongols, either. The Aday Kazakhs have more, and more diverse musical styles than the Azeris or Turkmens and their tunes substantially differ from the pentatonic musical styles of the Kazakhs living more to the east.

Let me summarize the conclusions drawn from the comparison of the folk music of Kazakhs in Mangyshlak in southwest Kazakhstan and those living in Bayan-Ölgiy area in Mongolia.

Melody contours. Apart from descending lament tunes, the first lines of Mongolian Kazakh melodies have a convex or concave curve, or a combination of the two tracing a hill-and-vale line. Also frequent are the more restless different up-and-down oscillating tunes, those reciting some neighboring tones or again others bouncing on a few notes. Though the second half of Mongolian tunes is lower than the first, one only exceptionally finds fourth or fifth correspondences between the lines.

In Mangyshlak the first line of the Aday Kazakh tunes moving on minor-character scales is typically convex; a gentler version of narrower compass can be found in the laments, psalmodic tunes and some narrow-range tunes. The first line of their wider compass two-lined la-pentatonic tunes and of the single noteworthy tune group ending on do traces a hill. This hill-shaped curve appears to be a characteristic line form that underlies the homogeneity of the Mangyshlak tunes. There are few tunes here that have a marked descent, or ascent or hill-and-vale shape. The rest of the “melodious” forms are almost wholly absent. All this widely differentiates this music from the versatile music of the Mongolian Kazakhs.

Let us compare the tunes of the two Kazakh areas since the melody progression or, more precisely, the contour of the first line.

The descending melody line of the Mongolian Kazakh laments is rare in this region which prefers finely arched lines, while the lines of the Aday Kazakh laments tracing shallow hills fit snugly among the other tunes there. The two lines progressing one under the other of the Aday Kazakh and Anatolian (as well as Hungarian) laments are structurally related with the lines ending on juxtaposed notes, but the tone sets are different. By contrast, the tone set of the Mongolian Kazakh laments is similar to Hungarian and Anatolian laments, but their structures are different. These laments can eventually be retraced to the combination of four gradually lower hill-shaped motifs. Progressing from high to low, the motifs are: (1) sol’-la’-sol’-fa-mi, (2) mi-sol’-(fa)-mi-re, (3) sol’/re-mi-re-do, (4) re-mi-re-do-si. These motifs are used by the laments of different ethnic groups as building block in the following way: Kazakhs of Mangyshlak: 1 and 1+2; Mongolian Kazakhs: 3; Anatolian Turks and Hungarians: 2, 3 and 2+3. Anatolian and Hungarian laments are closest to one another, the Mongolian Kazakh laments are like them but the realm of the Mangyshlak laments is different.

It applies to both Kazakh areas that the first line traces a well discernible hill or vale, or a clearly descending or ascending melody section. The more “melodious” lines of Mongolian Kazakhs contain two of the sections (of hill, valley, ascent, descent) at most. Repeated or varied motivic bar structures can often be discovered in these tunes: the rising-falling-rising wavy lines are often built of a b a bars. The shape that is most frequent in Anatolian and Hungarian folk music from among the mentioned ones is the hill. However, while in Anatolian and Hungarian tunes the rate of descending or stagnant lines is considerable, in Kazakh areas—except for the Mongolian Kazakh laments—such forms are rare.

The popular hill-and-vale wave in the first line of Mongolian Kazakh folk tunes also appears in Mangyshlak (South-Western Kazakhstan) but more rarely. Convex, hill-shaped first lines are massively represented in the southwestern Kazakh area, while they only occur—rarely, too—among the la-pentatonic tunes of Mongolian Kazakhs which are themselves very rare. Valley-shaped, concave first lines can only be heard among the Mongolian Kazakhs—rather infrequently and rarely in distinct form.

In both areas one can find rising first lines, but this musical solution is not frequent among every Turkic group. An ascending first line is always followed by a descending second line.

Many tunes move on the notes of bi-, tri-, or tetrachords. This may happen without clear schemes, but sometimes distinct motifs are repeated. That was seen for example with the popular psalmodic tunes of Mangyshlak whose common features are recitation on the notes of the do-re-mi trichord for a little while and the overall descending tendency of the whole melody, as well as the 5(b3)4 cadences. Such tunes are included in Anatolian and Hungarian folk music in large numbers (Example 11).

b) Anatolia (Sipos 1994: № 127), c) Hungary (Kodály 1937-1976: № 176)

Several terme tunes of Mangyshlak also belong to the recitative tunes; they are built of lines moving on two or three notes. Some of them remain on the do-re-mi trichord throughout the musical process, but some have a wider compass.

Mongolian Kazakhs also use a kind of psalmodic melody in which the first line moves in a higher register and then comes the recitation on the do-re-mi trichord. Apart from the similar melody contour, the tunes are also tied by the 7(b3)b3 and 7(b3)4 cadences; the difference is that the Mongolian Kazakh tune is do-pentatonic, the Hungarian and Anatolian examples are Aeolian in character.

The first line of many tunes in Bayan-Ölgiy moves up and down in tritony or tetratony. It is not easy to systematize these motions; what binds them together is the up-and-down steps within a fourth or fifth using the notes of pentatony (or the like). Twin bars within a line is not infrequent, and sometimes the whole tune is built of a single bar. It is important to note that such structures are often found among Mongolian Kazakh religious tunes and the tunes of a more recent style in Mangyshlak (Example 12).

In view of the enormous territory and the complexity of Kazakh ethnogenesis, it was easy to hypothesize that diverse musical dialects would be found here. Indeed, while the Kazakh tongue is surprisingly homogeneous despite the dialects, in music the divergences are considerable. According to Beliaev (1975) there are three main dialectal areas. The tunes of South Kazakhstan (the Semirechye, the area of Lake Aral and the Sir-Darya) are characterized by formal simplicity and rhythmic regularity. In the West, beyond the Ural and along the Caspian Sea lyrical solutions are predominant with broad melodies of wide compass, and the presence of termes and recitative forms is also typical. In the central parts of Kazakhstan there is a special wealth of tunes, advanced melodies, and complex verse forms.

The do-pentatonic and sol-pentatonic tunes of Mongolian Kazakhs are closer to the pentatonic Mongol-Tatar tune style, while most West Kazakhstan tunes move on scales including the minor third that are so popular in Anatolia (and in Hungarian areas). Data indicate that the music of Kazakhs in China is like the music of Mongolian Kazakhs with several variants in diverse areas of today’s Kazakhstan. In the two regions I studied the “closer” ethnogenesis was quite apparent, and probably that accounts for the fewer and relatively more homogeneous musical style. This is in sharp contrast with the extraordinary diversity of the Anatolian or Hungarian folk music.

Intricate relations have been discovered about the Kazakh laments. Some threads tie the Mangyshlak lament to its Anatolian counterparts, others connect the Mongolian Kazakh laments to Anatolia. At the same time there is—so far a single—Mangyshlak lament which almost perfectly tallies with the small form of the Turkish and Hungarian lament. It is an important finding that the tunes of psalmodic character are also widely popular in Mangyshlak, too. Many of the other similarities and differences derive from the fact that in Bayan-Ölgiy the do-pentatonic scale is prevalent while in Mangyshlak diatonic scales with the minor third is. Pentatony goes together with the agility of the tunes and decisively influences their character. This is also an aspect of the folk music of Mongolian Kazakhs that compares it to Chinese and Mongolian music, to the tunes in the Volga-Kama region and in some Hungarian pentatonic styles, while the music of Mangyshlak is closer to the Anatolian Turks, Turkmens and Azeris.

The folk music of the southwestern Kazakh area has not much in common with the broader ranged, mostly pentatonic Chuvash, Tatar, Bashkir, or Siberian Turkic, Uyghur, Mongol and Chinese tunes. In this music modest forms are preponderant, there are often free pre-strophic solutions. There are conspicuously few tempo giusto performed tunes, possibly related to the startling fact that the Kazakhs do not dance, either. Within the pentatonic musical world, the Mongolian Kazakh folk music represents a peculiar hue.

Kyrgyzs

Kyrgyz folk music, just like the Kazakh, is rather complex. Two large groups emerge from the tunes moving mainly on major-character scales. One is the twin-bar material retraceable to short motifs, which has a still lively richness in the area. The other group resembles the small form of the Hungarian laments. The Kyrgyz tunes can be ranged into five blocks of different sizes and significance.

The twin-bar tunes include the following groups: (a) tunes bouncing on the do-sol bitone, (b) tunes rotating round the middle note of the re-Do-si, mi-Re-do, etc. trichords; (c) the bekbekey tune group and Phrygian tunes with two short lines and re, do or mi cadence (which closely resemble populous Anatolian, Azeri and Turkmen tune groups moving on the Phrygian scale), (d) tunes starting with a descending or convex, hill-shaped line, with (sol’)-mi-re-do-sol descent or do-re-mi-(sol’)-mi-re-do-(sol) hill being the most frequent. Such twin-bar structures are frequent in the folk music of other Turkic groups, too. Finally, (e) tunes with a jump down at the end of the lines (do-sol, re-la or re-si-la closing patterns).

Tunes progressing along major-character scales can be divided into laments, 2-lined tunes and 4-lined tunes. In the first group we have laments and tunes whose genre and melody outline (e.g., kiz uzatuu or girls’ farewell) subsume them here. The simplest form of major-character Kyrgyz laments and girl’s farewell is characterized by a simply performed quasi-major line and its variants. These lines trace a hill of do-re-mi-fa | re-re-mi-fa-mi re | do skeleton which may be preceded by a sol-do jump up or followed by a do-sol leap. The two-core form of the Kyrgyz lament has longer descending, or hill-shaped lines performed parlando-rubato, cadencing on re and do. This is very similar to the small form of Anatolian, Azeri or Hungarian laments, although the more markedly hill-shaped lines of some Kyrgyz laments lend them a somewhat different character. It is a good indication of the deep embeddedness of this form in Kyrgyz folk music that several Kyrgyz tunes of short lines have the same character. The two-lined tunes of major character have the following groups: (5) main cadence and line 1 undulating on the mi-re-do trichord; (5) main cadence and line 1 tracing a tall hill with sol’/la’ peak; (6) main cadence (unlike in most Turkic music, the (6) cadence, even main cadence is not infrequent among the Kyrgyz), and finally, tunes with (7) and (8) main cadences with a higher first melody half. The typical cadential patterns of major-character four-lined tunes are 5(4)x, b3/4(5)5, 5(5)x, 6(6)6 and 5(5)5 as well as 7/8(4/5)x.

Owing to the unstable intonation of the third, too, there is close connection between the minor and major-character laments, so much so that they could have been discussed in one group. What was said of major-character laments applies to the rarer minor-character tunes having fewer forms. The main cadences of two-lined minor tunes are (4) and (5). The first line of four-lined minor character tunes keeps reciting within a narrow tonal strip, or it is convex, sometimes ascending. The typical cadence schemes are 5(2)x and 5/7(b3)x, 4(5)x, 4(4)x, 5(4)x and 5/6(5/6)x and 7/8(5/4)x. There is one major-character tune class whose first line is valley-shaped, ascending or undulating by touching on the tonic in mid-line; this feature separates them sharply from the rest of the Kyrgyz tunes. The larger subgroups of these Kyrgyz tunes—those with (4), 4(1)x and (5) cadences—are closely connected to the tunes of the previous class, although there are no laments among them. The cadences of four-lined tunes with an undulating first line are: 4/5(b3)x, 5(4)x and 5/4(5)b3.

Possibly the most important—and certainly the most colorful—element of Ramadan traditions is the singing of Ramadan songs. During the month of fasting the children go from house to house singing and collecting small gifts: in addition to money, candy, various seeds, fruits, etc. Though with smaller intensity than among the Kyrgyz, the Ramadan traditions are also observed by the Uzbeks, Kazakhs, the Ahishka, Uyghur and Anatolian Turks. The Kyrgyz Ramadan tunes deviating widely from their folksongs are introduced in detail in Sipos (2014).

Finally, there are some Kyrgyz tunes whose inner lines are a fourth or fifth higher than the outer lines; this kind of domed structure cannot be found in the archaic styles of Turkic people. The minor-character domed tunes have 1(5)5/4 cadences—that is, their third line also ends high. Line 2 is a variant of line 1 with a higher cadence, or it moves in a higher register. The latter is less frequent and also diverges wide from the typical form of Kyrgyz folksongs, while it more closely resembles, for example, Hungarian new-style songs. The cadence scheme of major-character domed tunes is b3(7)4/5/7, and their melodic progression also contain elements that deviate from the traditional Kyrgyz patterns.

Volga-Kama-Belaya Area

If we continue our overview and take a bird’s-eye-view of the music of Turkic group in the Volga-Kama region, we find a musical realm of a different character. The folk music of Tatar, Chuvash and Bashkir people is characterized by an almost exclusive use of whole or partial pentatonic scales and often descending melody outlines. The fifth-shift can also be found here, but this marked feature is only present in a 100 km circle of the Cheremis-Chuvash border zone, among the Cheremis of a Finno-Ugrian tongue only up to the limit of Chuvash Turkic linguistic influence. In the wholly pentatonic music of the Tatars there is no fifth-shifting, but there is fourth-shifting. As seen earlier, pentatonic fourth- or fifth-shifting on a mass scale occur in Outer and Inner Mongolia, which suggests that maybe it is the vestige of the Mongolian influence during or after the Golden Horde. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the fact that the Bashkir and Tatar uzun küy or long song also points towards Mongolian folk music.

The folk music of the region is highly complex with narrow and broad-ranged forms of diatony and pentatony, a wide spectrum of melody construction from the repetition of primitive motifs to strictly structured four-lined forms, etc. The distribution of these is, however, most uneven among the different groups.

Let us see what the researcher with first-hand experience of the area—László Vikár (1993: 33-39)—has to say about the music of this region. It is typical to Finno-Ugrian music to emerge from the repetition of very simple elements, but these primitive elements are repeated and varied in a highly sophisticated manner. Going from north to south, the strophes and melody lines become gradually longer and more regular. The traditional Finno-Ugrian tunes remain within the pentachord frame in quiet, sometimes monotonous, reserved performance. Under Turkic influence, the pentatonic scale and ornamented performance may sometimes occur—or even become predominant in certain areas. Still, the Finno-Ugrian stratum is dominated by a great degree of liberty, a meagre tone set, but powerful variation of the small motifs. Form, line length, syllable number and pitch intonation are all varied. They easily extemporize, do not regard the rigid limitations of strophic performance and a single tone set important. By contrast, the Turkic ethnic groups living here gladly sing, have several attractive strophic tunes whose compass reaches and even exceeds the octave. But obviously the Turkic groups also have simpler melody styles, some Turkic groups—e.g., Azeris, Turkmens and Dobrudja Tatars—having such tunes exclusively.

It is Vikár’s (1993: 33-39) observation that progressing from east to west in the Volga-Kama material, one finds increasingly more regular tune structures up to the Cheremis-Chuvash border (fifth-shift limit). Cheremis music is predominated by the so-called small form, Chuvash music by the three-lined structure constituting a transition between the free and more strictly built tune structures. Anyhow, underlying the diversity of tune forms in the region is simplicity. Disregarding now the repetitions, transpositions and smaller or greater rhythmic and melodic changes, we find one or two simple musical cores or a single motif remaining.

Lajos Vargyas (2005: 238-323) also surveyed the folk music of the Volga-Kama region. Below is a summary of his findings about the folk music of Cheremis, Chuvash, Mordvin, Tatar and Bashkir people living in this territory.

The songs of the Finno-Ugrian Cheremis (Mari) people are typically do-pentatonic, sol-pentatonic, and la-pentatonic without semitones in about equal proportions, with negligibly few mi-ending or re-ending pentatony. In the north one finds pentatony without semitones, where the small fifth-shifting form A4BAB is also typical. Some tunes only move on five, less frequently three or four neighboring notes of the pentatonic scale. The largest group includes fifth-shifting tunes, but they can only be heard in the Chuvash border zone where all the la-pentatonic tunes include the fifth-shift. Cheremis music is characterized by regular forms, the maximal observance of the frames of form-construction. Laments and children’s play songs are missing altogether. The tone set is simple, regulated; changeable intonation is not typical, possibly upon Turkic (Tatar) influence.